The Role of Food in Philippine Cuisine: A Culinary Journey

Introduction

Food, known locally as “pagkain,” is far more than daily sustenance in the Philippines; it is a vibrant thread woven through the nation’s identity. Each dish carries echoes of island geography, centuries of trade, and communal spirit. This article explores how Filipino fare evolved, the flavors that define it, and why it continues to captivate diners at home and abroad.

The Historical Evolution of Philippine Cuisine

Pre-Hispanic Influences

Long before overseas ships arrived, seafaring settlers and indigenous groups cultivated rice, root crops, and fruit trees, while coastal communities traded salt and dried seafood. Early kitchens relied on clay pots, open fire, and souring agents such as tamarind and vinegar, laying the groundwork for many dishes still enjoyed today.

Spanish Influence

Three centuries of Spanish contact brought onions, tomatoes, and slow-cooked stews that merged with local techniques. The technique of simmering meat in vinegar and aromatics evolved into what is now considered a national comfort food, while festive roasting traditions gave rise to centerpiece dishes at birthdays and holidays.

Other Influences

Merchants from neighboring regions introduced noodles, soy-based seasonings, and new ways to preserve fish. Later interactions added baking methods and canned goods, all of which Filipinos adapted to local tastes, creating hybrid plates that remain popular in roadside eateries and home kitchens alike.

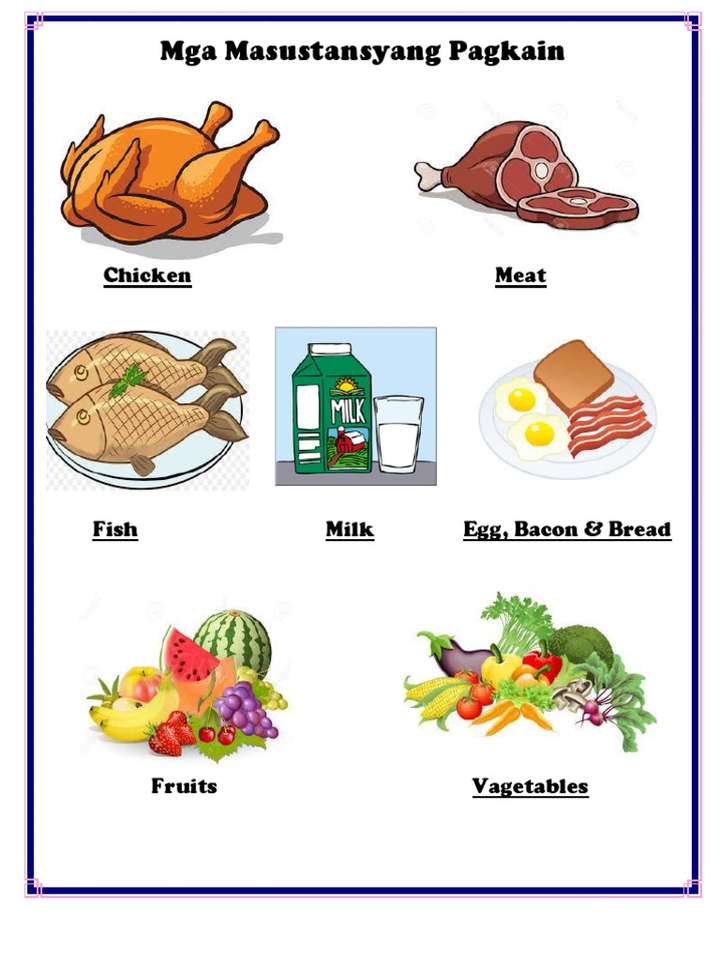

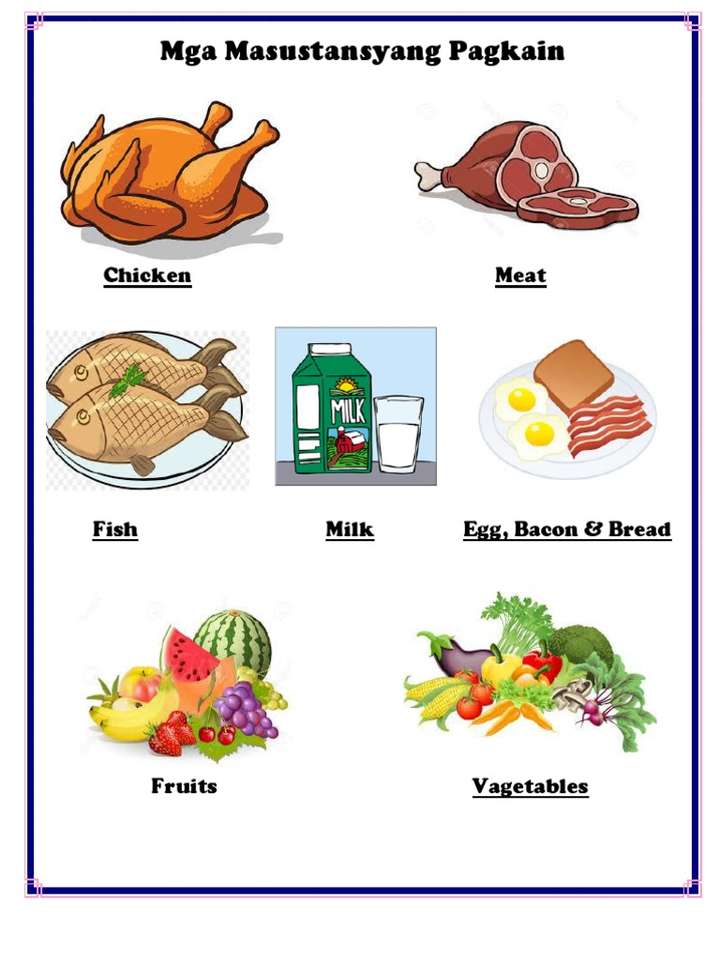

Unique Flavors and Ingredients

Adobo

Adobo showcases the Filipino knack for balancing sour, salty, and savory. Meat is gently braised in vinegar, crushed garlic, and spices until tender, then allowed to rest so flavors deepen. Each household claims its own ratio of ingredients, making every pot a personal signature.

Lechon

Whole roasted pig, golden and crackling, often takes pride of place at celebrations. Hours of slow turning over glowing coals yield juicy meat beneath a crisp shell, typically served with a tangy liver-based or vinegar dip that cuts through the richness.

Sinigang

Sinigang refreshes the palate with its light, sour broth. Whether built around shrimp, pork ribs, or vegetables, the soup relies on natural tart fruit to brighten the stock, demonstrating the local preference for lively, contrasting tastes in a single bowl.

The Social Aspect of Food

Family and Community

Mealtimes double as family meetings, where stories pass along with shared plates. Weekend gatherings and town fiestas overflow with colorful stews, grilled skewers, and sweet rice cakes, reinforcing bonds across generations and neighborhoods.

Food as a Form of Expression

Cooks treat plating as storytelling: banana leaves line bamboo trays, herbs crown soups, and sauces swirl into playful patterns. Such care signals respect for guests and pride in craftsmanship, turning even modest snacks into edible art.

Conclusion

From ancient barter systems to modern fusion pop-ups, Filipino cuisine continues to evolve while honoring its roots. Preserving heirloom recipes, supporting small farmers, and sharing meals with newcomers all ensure that the archipelago’s culinary heritage remains a living, breathing celebration of community and creativity.

Recommendations and Future Research

Culinary programs can weave regional foodways into broader coursework, giving students hands-on experience with indigenous produce and traditional techniques. Documenting family recipes and local fermentation practices safeguards knowledge that might otherwise fade with time.

Scholars and chefs are encouraged to explore eco-friendly sourcing—such as heritage rice varieties and underutilized seafood—to create dishes that nourish both people and the planet. By blending respect for the past with innovation, Philippine cuisine can thrive for generations to come.

In the end, every shared plate tells a story of resilience, adaptation, and joy. Honoring that narrative ensures the spirit of Filipino food remains as warm and welcoming as the smiles that greet each meal.